Palæoboreanic Technology

Copyright © 1999-2020 C.E. by Dustin Jon Scott

Introduction

Palæoboreanic technology eventually reached what we would likely regard as an approximately “Renaissance” level of technology before finally dying out.

Materials

The Palæoboreanic people knew how to work with a variety of metals, including gold, silver, tin, copper, bronze, brass, and iron. They could produce clear glass, legendarily attributed to a failed attempt to cast an obsidian blade, from an extremely early phase of their technological development, allowing for clear panes of glass for windows, lanters, and even spectacles.

See also Borean Materials.

|

Glass — The discovery of glass was credited to “the Folly of King Beowyn”. According to legend, when King Beowyn first learned the art of casting iron and bronze, he immediately noticed that the edges of the arrowheads and speartips could not be made nearly as sharp the obsidian spearheads and arrowheads of his people, and wondered if he could cast obsidian in the manner of a sword to create a blade sharper than the bronze and iron blades he had just learned to make. This appeared to work, however the resulting blade was so brittle that it shattered upon its first attempted use. He gathered the shards and re-cast them, to the same result. He attempted this many times over, discovering that with each re-casting the obsidian became increasingly transparent. Finally, when he'd found himself with a nigh-crystal-clear product, King Beowyn realized that though he’d failed to create a usable obsidian blade, he had accidentally stumbled upon an invention of great utility. This is sometimes also called “King Beowyn’s Fortunate Folly”. |

|

Metals & Metalworking — the Palæoboreanic people experienced their iron age at roughly the same time as their bronze age, as has since been the case for certain African tribes (this differs from later European and Middle-Eastern tribes, who had a prolongued bronze age before they learned to work with iron). In spite of this, iron remained in short supply and the majority of armor, weapons, agricultural tools, and the like, were mostly made from bronze or brass, while iron remained a specialty material mostly reserved for well-to-do. Much of the iron worked with was a dangerous, possibly radioactive variety that Dwarves mined from the Elvenbane Delves called "cold-iron". Cold-iron could burn the skin of the Fairikin on-contact and prolongued exposure would often result in hair and tooth loss along with bleeding from multiple pores and orifices; Boreans who worked with cold-iron frequently over many years would generally develop growths and tumors, although other Werish races such as Dwarves and Ogres were apparently immune to the effects. |

|

|

Textiles — the ancient Boreans used reeds, hemp, flax, wool, and other materials to make a wide variety of textiles. Weaving and knitting were the most common techniques used. Sometimes natural fibers would be inter-woven with fine strands of gold and silver (a technique that would later be independently developed by the ancient Egyptians, but which has since been lost to history). Fabrics we would recognize today include wool, hemp, linen, silk, sendel, and baudequin. |

Tools

See also Borean Tools.

|

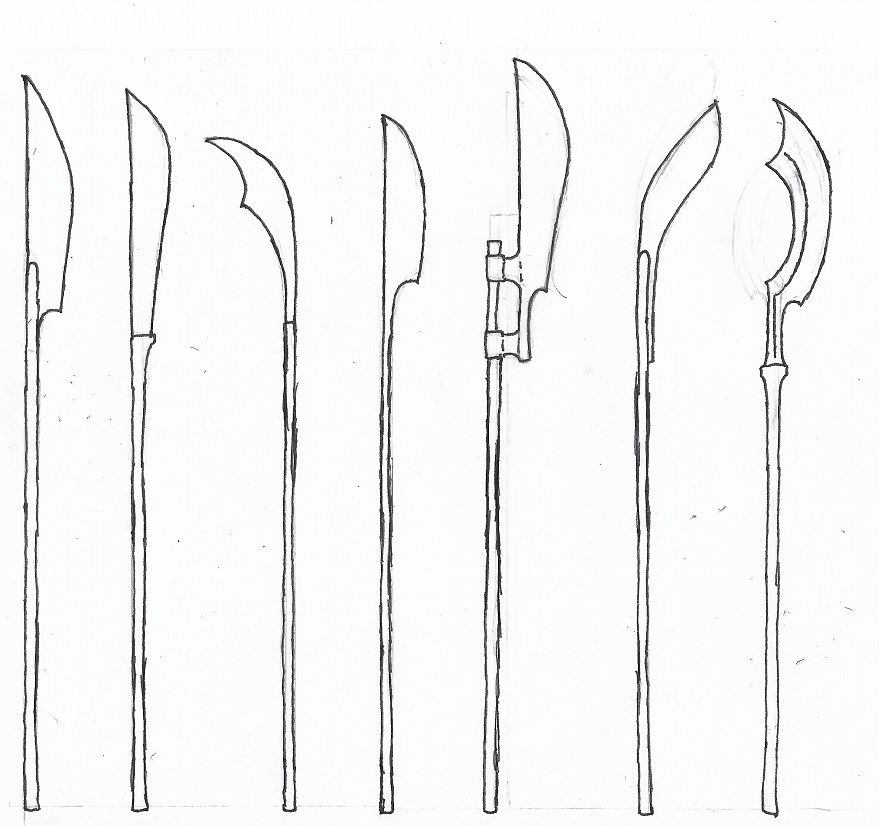

Borean Poleblades — The Palaeoboreanic peoples used long-handled blades in their agriculture, as well as bladed polearms based on them in combat. Depicted here are some of the more common blade varieties. |

|

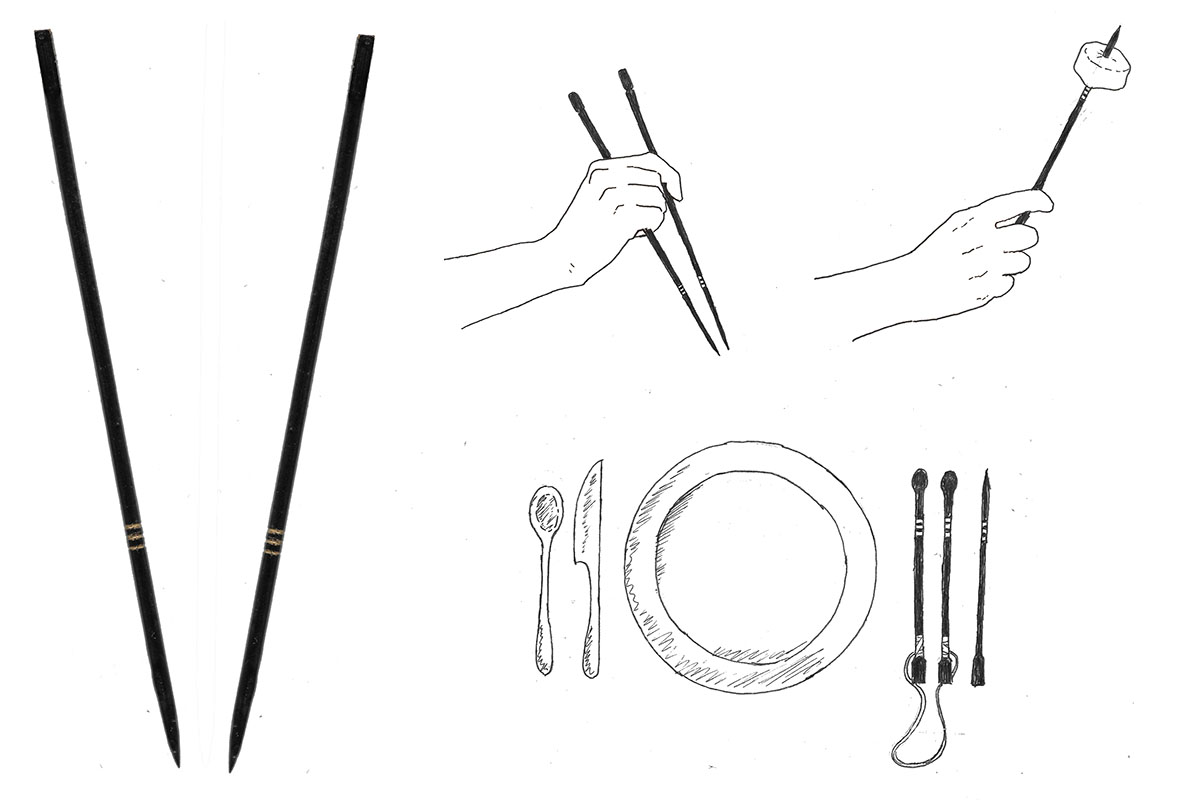

Borean Cutlery: Tines — The Palaeoboreanic peoples had a very distinctive eating utensil: the tine. Tines were often used in pairs, similar to modern chopsticks, although poor and/or uncultured individuals tended more often to use them singly in the manner of a skewer, stabbing their food crudely. Wealthy and/or cultured individuals tended to have specialized varieties: blunted pairs of "gripping-tines" connected by a chord or chain, and single, finely pointed "skewering-tines". |

Architecture

The Palæoboreanic people seemed to have an intuitive knowledge of arches and buttressing even from an early stage when the most "civilized" settlements were still stacking rough, unhewn stone, occasionally in combination with a cob-like mortar, for their largest and most impressive buildings. Development of vaults and domes came later. Late-stage Palæoboreanic peoples were creating large structures comparable to the architectural achievments of the ancient Greeks, Egyptians, or Romans, but incorporating elements we associate more with late Medieval or early Modern architecture & decor, such as glass windows.

See also Borean Architecture.

|

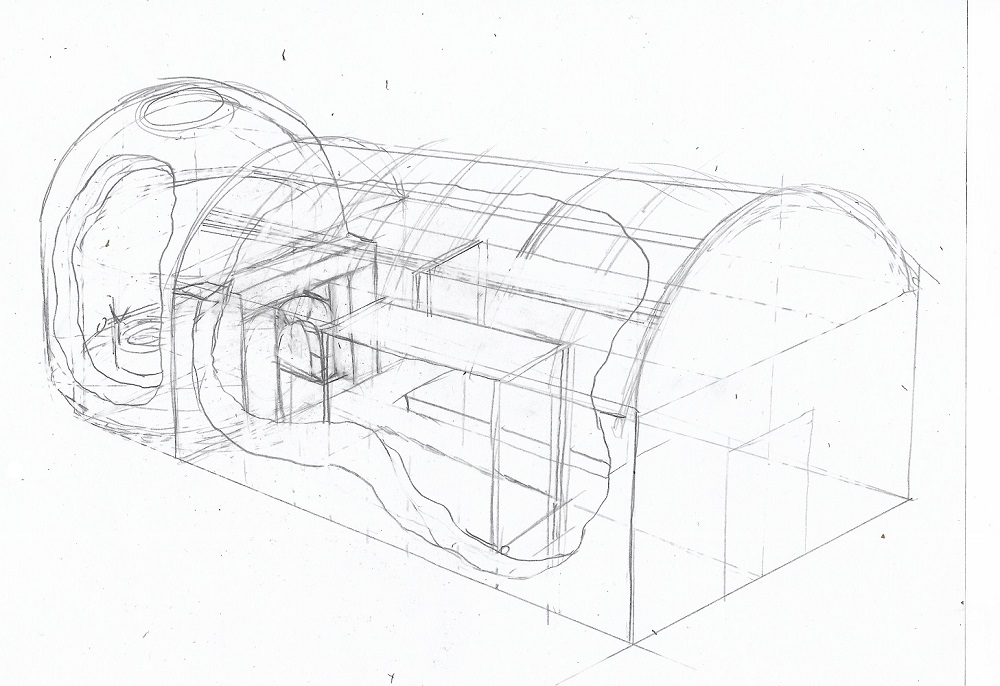

Borean Dwellings — a typical Borean rural dwelling was composed of between two and five adjoined buildings, including a domed building constructed of fire-resistant material with a smoke-hole in the roof, often referred to as a kitchen, an atrium, or a hearth, a large living room or hall in which an extended family group or a band of friends or colleagues would sleep for the majority of the year (except on cold winter nights, when people would tend to sleep in the hearth/atrium). Other rooms would adjoin to the hearth/kitchen, and the most commonly seen was small bath-house; other adjoining rooms might include a cannery, an armory/toolshed, a grainery, or a slaughtering and butchering room. Urban dwellings for average citizens of most Borean cities lacked their own kitchens/atria, and were often but a single room in a larger structure. |

Borean Attire

See also Borean Attire.

|

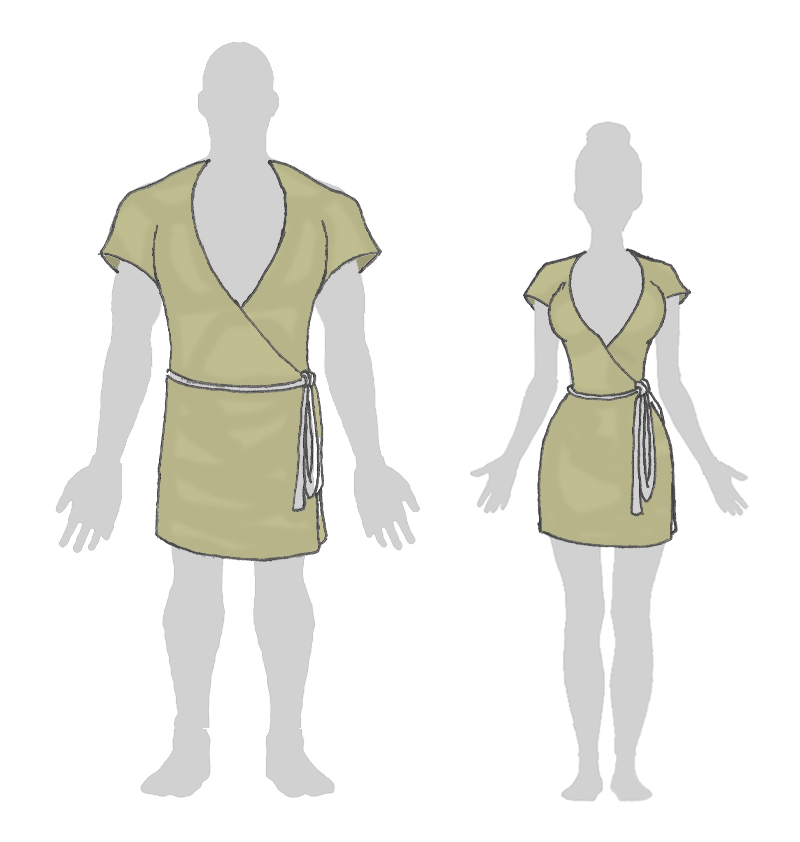

The Borean Open-Chest Tunic |

|

The Trinarian Monastic Scapular (formal) |